Cause (BRONZE)

Client Credits: Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Client: Ontario Ministry of Transportation

Marketing & Advertising Lead: Debra Merowitz

Director, Communications: Kimberley Bates

Manager, Road Safety Marketing Office: Andrew Davidson

Communications Coordinator: Andrew Miller

Manager, Editorial & Corporate Services: Stan Sutter

Agency Credits: john st

Agency: john st

Executive Creative Director: Stephen Jurisic, Angus Tucker

Copywriter: Sanya Grujicic, Jacob Greer

Art Director: Andrew Bernardi, Denver Eastman

Account Director: Cheryl Carty

Strategist: Colin Carroll

Account Executive: Zalona Caruso

Producer: Sharon Langlotz

Production House: OPC

Director: Nicolas Monette

Director of Photography: Bobby Shore

Executive Producer: Donovan Boden

Line Producer: Isil Gilderdale

Editorial: Saints Editorial

Editor: Mark Paiva

Assistant Editor: Michael Orfori-Attah

Executive Producer: Stephanie Hickman

Online and Colour: The Vanity

Online Editor: Sean Cochrane

Colourist: Andrew Exworth

Audio Production: Boombox Sound + Music

Voice Director and Music Producer: Stephanie Pigott

Sound Engineer: Ryan Haslett

Executive Producer: Umber Hamid

Social Video Production: 172 Productions

Videographer: Matthew Johnson

Executive Producer: Cynthia Heyd

Media Agency: PHD Canada

Section I — CASE PARAMETERS

| Business Results Period (Consecutive Months): | June 2016-October 2016 |

| Start of Advertising/Communication Effort: | June 2016 |

| Base Period as a Benchmark: | New effort – benchmark is from start date |

| Geographic Area: | Ontario |

| Budget for this effort: | $3 – $4 million |

Section IA — CASE OVERVIEW

Why should this case win in the category (ies) you have entered?

Ontario has a distracted driving problem. Stories of collisions and death appear constantly on the news and many of us have had a near-miss with a driver who was staring at their phone. The stigma of driving intoxicated has been well-established after years of public messaging, but Ontarians, especially young Ontarians, still drive today while using their phone with regularity. It’s a great public danger not just for drivers, but for all of those who share the roads.

We conducted research to understand how people thought about distracting driving. This led us to understand that drivers, particularly younger ones, fear something more than death; they fear living as a quadriplegic. We showed that distracted drivers would have to live with the devastating consequences, resulting in surprising, compelling creative for this category.

This is a ‘cause’ case that didn’t just raise money for new research, or get people to care about a charity they hadn’t yet considered, this is a case that has potentially saved the lives of many Ontarians. Research shows the link between the campaign and not just attitudinal changes, but behavioural changes with 7% more Ontarians now actually reporting that they don’t use their phone while driving.

Section II — THE CLIENT’s BUSINESS ISSUES/OPPORTUNITIES

a) Describe the Client’s business, competition and relevant history:

One of the many things the Ministry of Transportation for the Government of Ontario is charged with is keeping our roads safe. In concert with law enforcement, they encourage safe driving. And through the course of many years, they’ve been able to curb once ordinary dangerous behaviour, drinking and driving. The recent flourish of cell phone overuse has created a whole new issue, distracted driving – driving while using a phone. Recent studies have shown that distracted driving now kills more people than drinking and driving, but in a culture where constant phone use is become normative, it was hard for people to believe. While the conversation around distracted driving had started to move from the fringe to the mainstream, many people didn’t take it that seriously. The Ministry needed to show Ontarians that distracted driving was a problem, a problem with potentially serious consequences.

b) Describe the Client’s Business Issues/Opportunities to be addressed by the campaign:

Ontario has a distracted driving problem. Stories of collisions and death appear constantly on the news and most of us have had a near-miss with a driver who was staring at their phone.

And the problem is getting worse. Someone is injured in a distracted driving collision every 30 minutes in Ontario. And in 2016, deaths from distracted driving were expected to exceed the death toll from drinking and driving. Unsurprisingly, it was young drivers, those least experienced and most connected to their phones, who were the worst offenders.

The challenge was simple but not easy: get drivers, especially younger drivers, to put down their phones while behind the wheel.

c) Resulting Business Objectives: Include how these will be measured:

The goal of the campaign was to increase the awareness of distracted driving as a serious issue as young drivers didn’t currently see it to be one, and in doing so, get them to put their phones down.

We would measure success by first looking at awareness levels recorded in the government’s omnibus survey post-campaign launch as well as looking at the number of hits to the website and views on the digital video version of the spot.

As we knew the campaign would be for naught if it didn’t result in drivers putting down their phones, the key metric in pre and post testing was the amount of people reporting to not use their phones while driving.

Further measures would include earned PR and social interest around the issue/campaign as measured by online views, shares and engagement.

Section III — YOUR STRATEGIC THINKING

a) What new learnings/insights did you uncover?

Young people today view their phone as an extra limb. Quite literally. A study conducted by Pew Research reported that the majority of respondents in an online poll would rather give up a finger than give up their phone for life.

They are bombarded with notifications throughout the day and the temptation to check their devices doesn’t go away when they get behind the wheel. In an age of instant gratification, they feel compelled to respond to any post, like, or comment immediately, regardless of what they might be doing at that time.

So if we were going to help change this habit, we had to find an idea that would be motivating enough for them to think twice.

Early in our research, we learned that most young people understood that distracted driving was dangerous. But when asked why they continued to do it, many of them rationalized their behaviour by saying “I’m only looking at my phone for a few seconds.” In other words, they didn’t think that what they were doing was dangerous. Yet a study has shown that taking your eyes off the road for even two seconds increases your crash risk by 24 times.

We had to make them understand that even those two seconds that you took to glance at a text or social post could mean the difference between life and serious consequences. That a small decision could lead to a big impact.

b) What was your Big Idea?

Distracted driving is incredibly common and we do it because we can rationalize the action in such a simple way.

“It just takes a second. Just a quick little glance.”

But that second is all it takes. It happens fast.

c) How did your Communication strategy evolve?

Key to the idea was that the “It” of “It happens fast” wasn’t death, but something young people considered far worse – paralysis. Focus groups with youth told us they’d rather be dead than paralyzed, where the freedoms that they were just beginning to enjoy were no longer theirs. So a key strategic input into creative was to not show the ultimate consequence, death, but show that they may actually have to live the rest of their lives being paralyzed from distracted driving. That they’d have their life altered forever and have to live with their mistake.

d) How did you anticipate the communication would achieve the Business Objectives?

Using a powerful visual image and a relatable situation and character, we created empathy without lecturing or preaching.

The target was youth. We knew what scared them worse than death, and that portraying that would compel them to understand that these consequences could happen to them, and happen to them that quickly.

If we could convince them that this little thing could have great consequences, what initially seemed like a big behaviour change would actually become a pretty small ask. The thinking was that the consequences they so feared would outweigh their need to check the phone.

Section IV — THE WORK

a) How, where and when did you execute it?

The campaign launched June 16, 2016 with a video that ran on TV, in theatres and online. A social media push then rolled out over the summer with content created exclusively for each platform—from GIFs to hyperlapse videos.

The launch video shows a young driver glance at his phone, run a red light and get T-boned by a truck. In an instant, the driver is thrown from the vehicle and lands in a wheelchair in the room of a long-term care facility. The transition from the seat of the car to the seat of a wheelchair happens in less than a second.

Given the ad would be featured in pre-roll, we were very conscious of making sure the crash happened before the 5 second ‘skip this ad’ prompt – knowing that it would be engaging enough from that point on to watch the whole way through.

The media plan also included a 60-second cinema spot where movie-goers got to see what happens to the young man now managing the reality of his new life. The theatre environment gave us the perfect opportunity to force a captive audience to consider what life as a quadriplegic would be like.

Spotify and radio ads were also created to help round out the campaign, and to reach drivers in the most relevant environment – their cars. There were three different audio executions, all targeting different distracted driving behaviours – checking maps, liking a post or choosing a playlist for the gym.

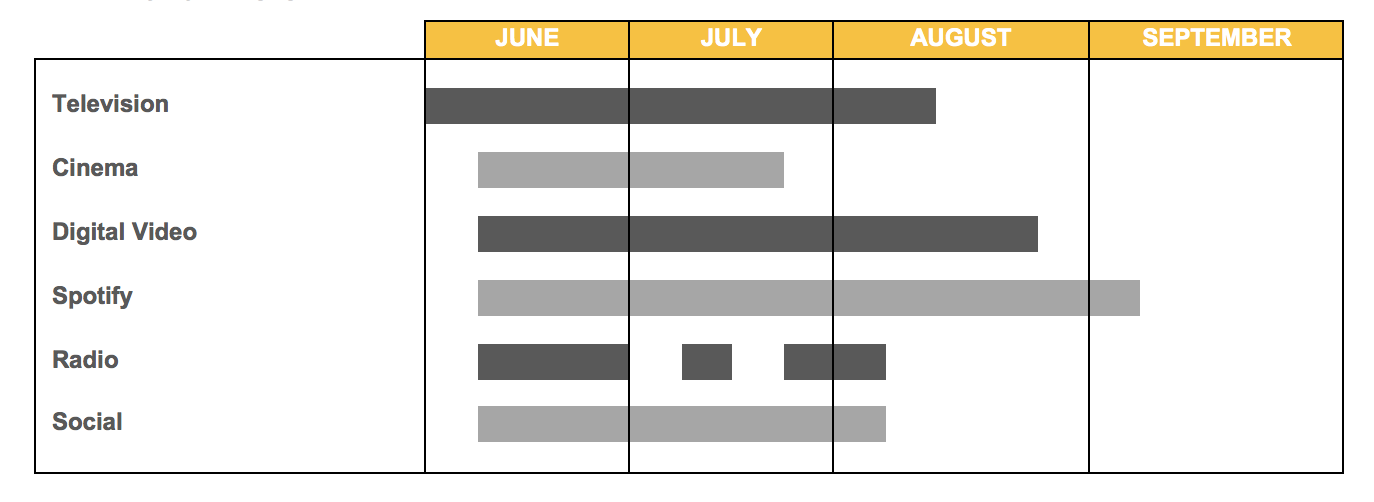

c) Media Plan Summary

Section V — THE RESULTS

a) How did the work impact attitudes and behaviour?

The campaign worked hard to deliver increased awareness of the seriousness of the issue with young drivers. According to the government’s most recent Omnibus survey results, completed in September at the conclusion of the campaign, we saw:

- 8% increase in number of people who reported distracted driving as a serious concern

- More people reported “social stigma” as a reason for not driving distracted

Importantly, the campaign changed how Ontarians acted behind the wheel. It delivered a:

- 7% increase in number of people who reported not using a phone while driving

b) What Business Results did the work achieve for the client?

- There were over 2 million views of the launch video

- The video recorded the highest ever recall for an Ontario Government ad (74%)

- The video outperformed YouTube’s benchmark for recall by 80%. Among those who viewed the whole ad this number spiked to 150%. Both numbers qualified for YouTube “Best in Class” Distinction

- Searches for “distracted driving” and “phone while driving” spiked 380% and 2900% on Youtube and Google during the campaign period showing not only engagement, but interest in the cause

c) Other Pertinent Results

- The #PutDownThePhone hashtag (created for and used exclusively for this campaign) was mentioned over 4,500 times in the first three weeks of the campaign

- The campaign wildly outperformed Ontario government social media benchmarks, and engagement of any previous @ONGOV campaign:

- 387% more retweets

- 203% more video views

- 393% more completed video views

d) What was the campaign’s Return on Investment?

With millions of Ontarians seeing and remembering the ad, and 7% more now reporting that they’ve stopped using their phone while driving, the creative has potentially saved many lives.

Section VI — Proof of Campaign Effectiveness

a) Illustrate the direct cause and effect between the campaign and the results

- In Ontario, the only communication at the time around distracted driving came from the campaign or the aforementioned earned media surrounding the campaign.

- Pre and post omnibuses showed recall of 74% for the campaign, with 7% more drivers in just four months saying they wouldn’t use the phone.

- The campaign was so provocative that CTV news aired a two-minute segment on distracted driving, featuring the :30 TV spot.

- Influencers, with no connections to the campaign or the Ministry, such as Ben Mulroney, were compelled to share the campaign to their personal social networks resulting in increased campaign exposure.

b) Prove the results were not driven by other factors

Campaign spend vs. history and competition:

- This was the first distracted driving campaign by the Ministry of Transportation, not a cumulative effort.

Pre-existing Brand momentum:

- There were no other distracted driving campaigns from the RCMP, OPP, other enforcement or advocacy agency in Ontario.

- There were no other distracted driving campaigns that either spilled into Ontario or created a cultural conversation that impacted Ontario

Pricing:

Not Applicable

Changes in Distribution/Availability:

- Phones did not become harder to use or heavier; there were no new technological advances limiting usage during driving during this campaign.

Unusual Promotional Activity:

None

Any other factors:

None